2. Program Design#

2.1. Key Concepts#

Key concepts in this document include

Mission alignment. Explicitly designing programs before seeking to fund them helps businesses and organizations stay true to their missions. Without a well-designed program aimed at achieving long-term goals, the ever-present need to raise money can push you to pursue funding opportunities that are only peripherally related to your purpose. This “tail wagging the dog” scenario is less likely to occur when your team has gone through a thoughtful design process and has a document to refer back to when deciding whether or not to pursue new opportunities.

Program vs. project. A project is a set of activities a team implements to achieve a specific objective. A program is a set of related projects, each with its own objectives, that work in concert to achieve a wider goal(s). A team guided by a well-designed program will carefully select projects based on their potential to contribute to institutional goals. Also, thoughtfully choosing projects can allow organizations to maximize finite resources—people, equipment, supplies, and money—thus increasing productivity and operational efficiency.

Acknowledge assumptions. All programs and projects have inherent assumptions in how they are implemented. Acknowledge these in your theory of change and periodically review whether they are correct. In other words, implement the tasks and interventions to solve the problem or create a solution to a problem that leads to the (assumed) intended outcomes.

Iterate and scale. Start small, experiment, and scale your successes [Bunch, 1982]. Scaling successes is not just about expanding; it involves planning and cost estimates across a wider scope/region, feasible analytical methods, and strategy to theory of change linkages [Salafsky et al., 2021].

2.2. Background#

The Forest Business Alliance (FBA) created this chapter to help grant seekers, program/project managers, and business owners design projects for submission to CAL FIRE’s Wood Products and Bioenergy Business and Workforce Development Grant Program. These guidance documents may also be useful for the USDA Forest Service’s Wood Innovation Program and other grant programs.

However, while providing technical assistance to businesses and nonprofits, we realized there was too much emphasis on creating projects to respond to proposal requests. Many organizations were developing projects without considering how they fit into a program or the broader organizational purpose, or, at worst, chasing funds without a plan or organizational priorities. Therefore, the guide emphasizes taking a step back from project planning to consider how it may fit into programmatic priorities and how you may need to retrofit strategic-level priorities in your organization.

Important

Program = A long-term collection of interrelated projects designed to achieve strategic goals and supporting objectives.

Project = A time-bound endeavor undertaken to produce a specific output or deliverable. A suite of projects should contribute to program goals.

A project may be analogous to building a house, whereas a program, depending on its complexity and scale, could be creating a neighborhood or city.

Competitive grant proposals are built around well-designed projects rooted in and contribute to thoughtfully planned programs. Projects that are well-designed are most effectively identified through proactive program planning. Program planning moves from the big picture (problems, needs, overarching goals, and desired outcomes) to an action-oriented project scale (what will you do to achieve the goals and outcomes, how long will that take, and how much will it cost).

This guidance document and the accompanying worksheets are intended to be used step-by-step to move you through the following design process:

Situation assessment

Theory of Change

Goals & Objectives

Monitoring (see monitoring chapter for more detail)

Budget

Implementation

Please keep in mind that program design is iterative and dynamic. As you add detail and progress, the information you input during prior steps may need to be revised.

We used numerous publicly available sources to create the project design and monitoring templates. We adapted information to create resources suited to the CAL FIRE Business and Workforce Development Program grant program. The Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation, developed by the Conservation Measures Partnership [CMP, 2020], and ProPack I: Project Design Guidance for Project and Program Managers, developed by Catholic Relief Services [CRS, 2015], are among the key sources we relied upon to develop this chapter.

Caution

The templates and information provided are for reference only. While FBA has made every effort to provide up-to-date and correct information, we make no representations concerning the contents.

2.3. Assessment#

Program planning typically begins with a participatory assessment of your business and organization and with the board, stakeholders, and clients. Conducting a thorough situation or problem analysis is central to your assessment. Your organization or business should review available evidence to complete your analysis, identifying the direct threats, core problems, and indirect threats, also known as drivers and causes. Evidence can be in many formats, for example Conservation Evidence, local studies or research on forest health, interviews with experts who possess historical knowledge and experience, or proven projects, pilots, or technologies with data to back up their outcomes.

A new or revised assessment should be completed when preparing grant proposals, designing new programs, or when several years have passed since a previous assessment.

Important

Situation Assessment = A model of the system in which conservation programs are taking place and trying to effect change [Salafsky et al., 2021].

We recommend you review pages 13 through 24 of the Open Standards [CMP, 2020], which provides an excellent primer on assessment.

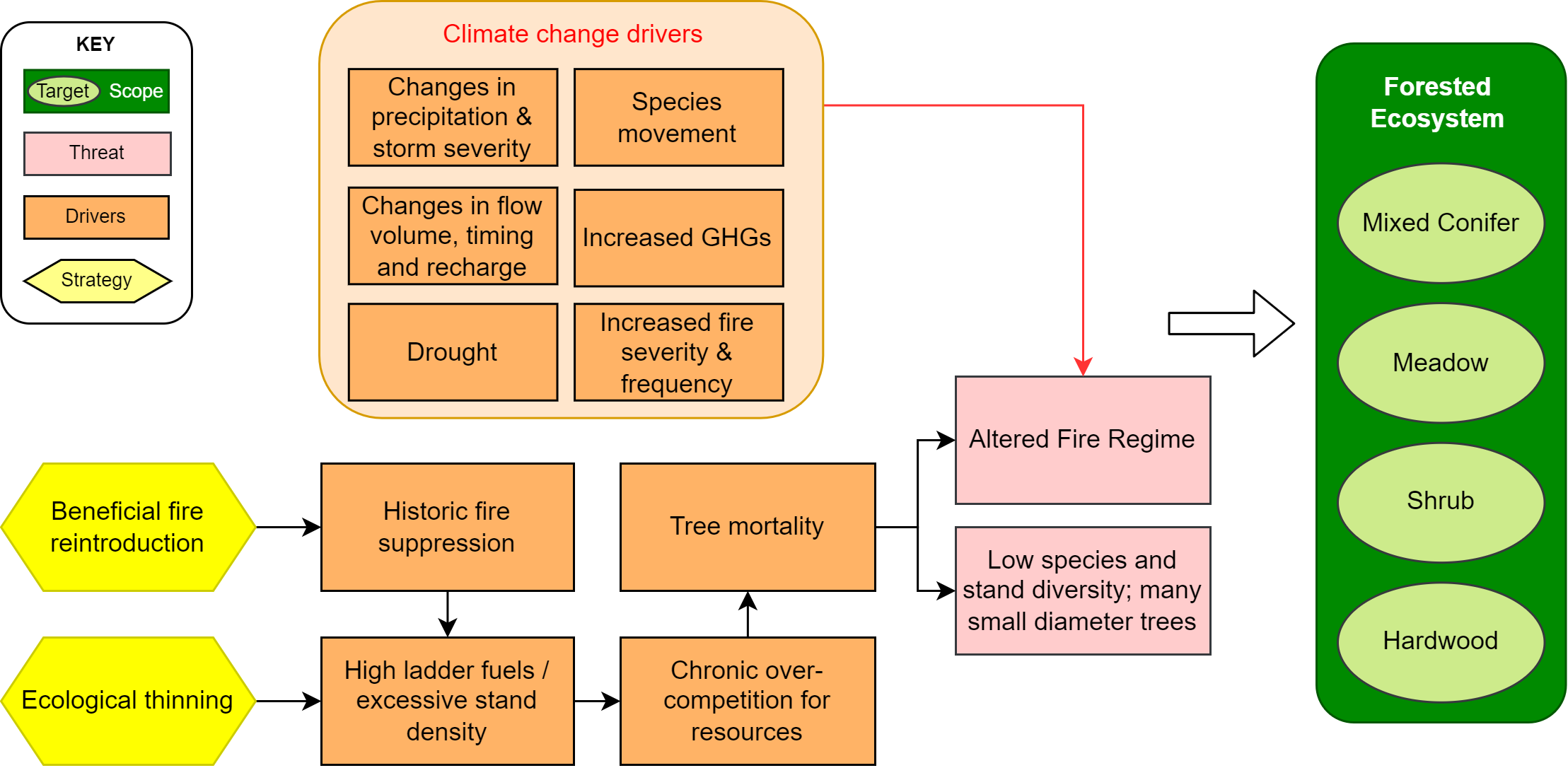

Fig. 2.1 Simplified forest health situation model.#

A situation model is a tool that visually portrays the relationships among the various factors in your situation analysis (Fig. 2.1). When presented visually, this analysis is more powerful. Both tools can explore and ultimately illustrate a program and its context. The model should illustrate the main cause-and-effect relationships and include the most important details, yet be as simple as possible. To the degree that it is feasible and useful, you should identify the actors behind key factors and discuss assumptions between the relationship factors. For example, in Fig. 2.1 arrows are essentially assumptions about the relationships between boxes in the assessment, e.g., tree mortality leads to increased fuel in a stand and alters the fire regime, especially in the absence of fire.

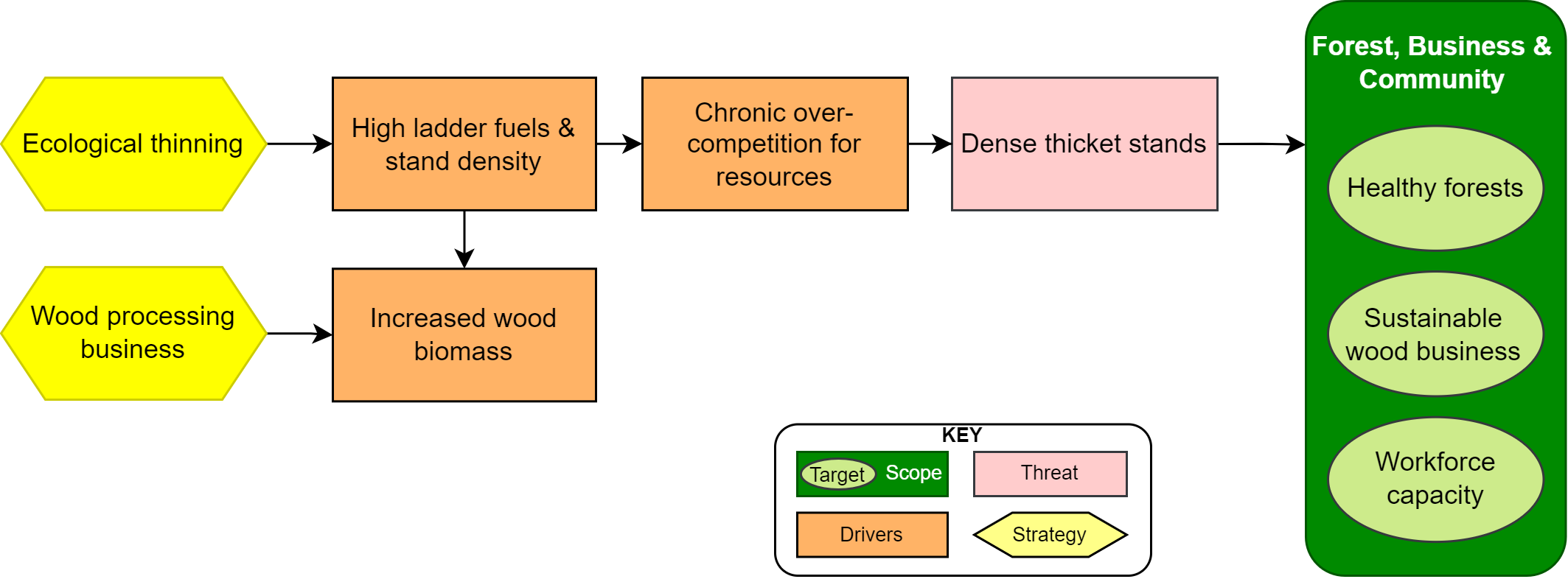

Although Fig. 2.2 depicts a conservation-focused model, a business can easily adapt it to suit its business model. The drivers and threats to healthy forests will remain the same in a forested system, but the strategy, scope, and targets may change. For instance, a wood products business may be focused on utilizing the wood removed by thinning projects and possibly increasing workforce capacity. Adapting the situation model to a forest business may look like Fig. 2.2.

Fig. 2.2 Wood products business situation model.#

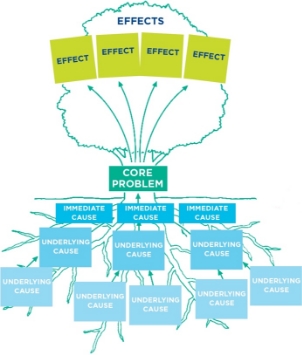

Design teams frequently use assessment findings to construct problem trees (Fig. 2.3). These causal diagrams help you identify and study core problems by identifying their immediate and underlying causes and their negative effects. This analysis, in turn, allows you to identify solutions and desired outcomes that will address the problems rather than their symptoms. A problem tree is also useful for understanding the linkages between your program actions and desired outcomes.

Fig. 2.3 Problem tree.#

Tip

Creating a Problem Tree

Problem tree analysis is ideally done with stakeholders at a participatory workshop. Participants write problems, immediate causes, root causes, and effects on sticky notes or note cards. Each card should contain only one item. This allows participants to move the cards around and discuss where they best fit within the problem tree.

Once you have created your situation model or problem trees, review the logic by asking these questions:

Does each cause-effect link make sense? Is each link plausible? Why or why not?

How well have the causes connected to the roots? Are there any unidentified root causes?

What appears to be the relative contribution of each causal stream to the problem/threat? Do some causes appear more than once? Why is this?

2.4. Theory of Change#

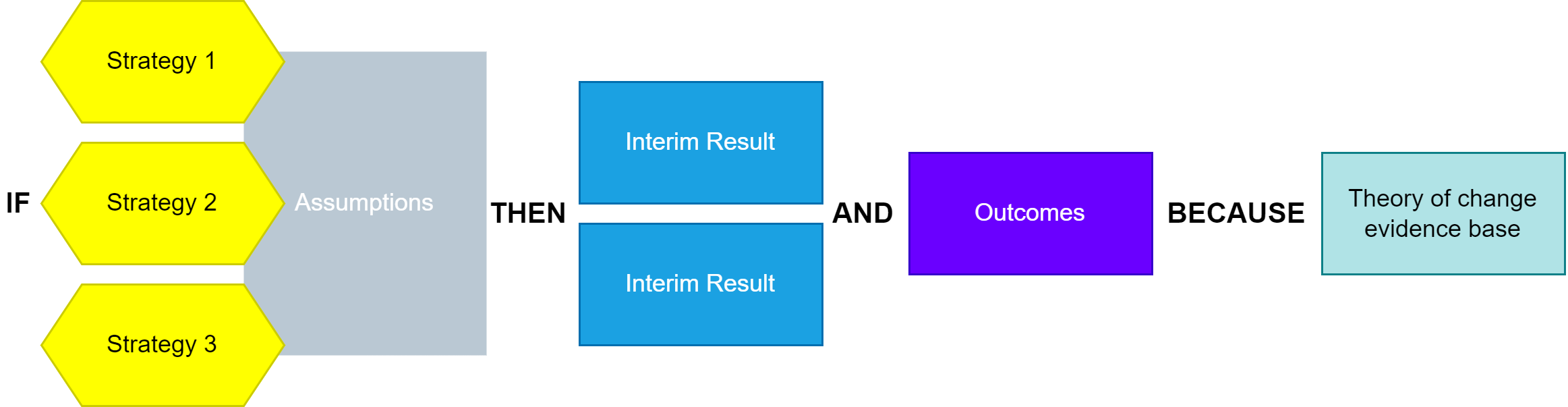

A Theory of Change bridges the problem analysis visualized in the problem tree(s) and the proposed responses reflected in the project’s results framework or ProFrame Fig. 2.4. The theory of change clarifies why you believe the selected project strategies will work in the project context and justifies and checks the logic and feasibility of the change hypothesis. A theory of change can be expressed in narrative or diagrammatic form.

Note

A narrative Theory of Change is a concise, explicit explanation of:

“IF we implement strategies 1, 2, and 3 and our assumptions hold true THEN, we will achieve the following interim results and outcomes BECAUSE of a defensible/cited evidence base”

With this structure, the theory of change clarifies how (if–then) and why (because) the project team expects or assumes that certain actions will produce desired changes for individuals, groups, communities, or institutions in the environment where the project will be implemented (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4 Simplified theory of change.#

The theory of change is not simply a narrative description of the results framework because the results framework only reflects the elements (the “ifs” and “then” parts) that the project will deliver, whereas the theory of change also states those actions or contributions critical to the project success but which you expect other actors to deliver. In other words, the theory of change reflects both the results framework and the project’s hypotheses and assumptions. Remember that the theory of change can be developed for different levels of the objectives hierarchy. A “high‑level” theory of change articulates how achieving the project’s objectives will contribute to longer‑term, broader, lasting change (project’s goal). You should minimally create a theory of change at this level. However, it may be necessary to create links from all project strategies to outcomes.

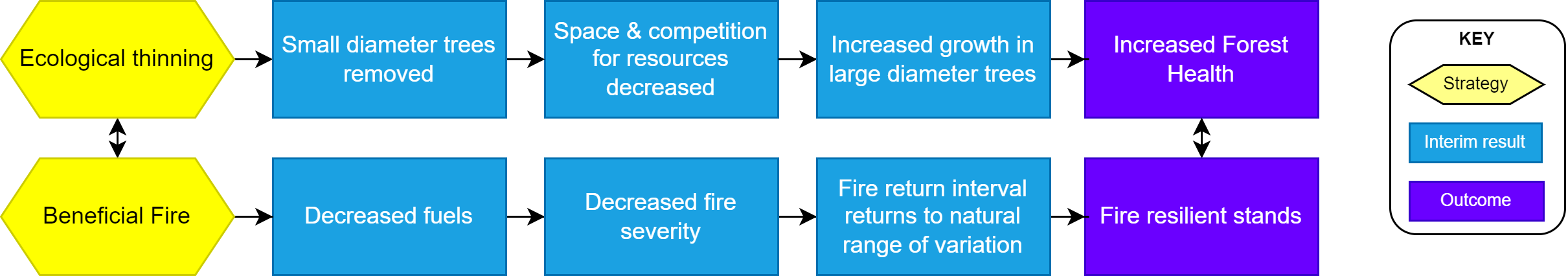

2.4.1. Results Chains#

Instead of a narrative theory of change, you may use a results chain, a visual diagram of a theory of change (Fig. 2.5). The results chain shows the strategies identified in the situation model and connects them to interim results and project outcomes.

Fig. 2.5 Results chains are a visual diagram of a theory of change showing anticipated outcomes [CMP, 2020].#

A more specific example of workforce capacity building is shown in Fig. 2.6. Once you have finished developing all project results chains, you can write your goals and objectives.

Fig. 2.6 A simplified workforce capacity results chain.#

2.5. Goals & Objectives#

Goals and objectives are often reversed, conflated, or used interchangeably by organizations, businesses, and agencies. Goals and objectives are distinct, important planning terms that identify programmatic success when conceived and well-written, e.g., how you want the world to change. Below, we provide guidance on creating statements for each level. Review CAL FIRE’s required metrics before you develop your goals and objective statements. Reviewing and understanding them is necessary for creating goals and objectives that align with CAL FIRE’s goals.

Goals are the high-level, long-term results and impacts an organization or business seeks to achieve. Derived from the scope of your situation assessment, they represent the desired status of the specific targets identified. Like objectives, goals are specific, measurable, and time-bound but typically over a much longer period, e.g., decades rather than months or years. Unlike objectives, the project’s goal statement is usually general and abstract, describing a desired state beyond the project’s life. For this reason, a goal will not have an associated indicator. Program goals are the nexus for your organization’s projects.

Example

By 2035, forest health will be significantly improved in California’s Central Coast region through management techniques such as thinning and prescribed fire.

Objectives represent the higher-order changes in systems, communities, or organizations that can reasonably be achieved during a project’s time frame and provide the building blocks to achieve goals. Well-written objectives are SMART = specific, measurable, achievable, results-oriented, and time-bound and are tied to the intermediate results and outcomes in a theory of change or results chain. In many projects, objectives reflect the benefits expected to occur by the end of the project as a result of behavioral changes at the interim results level. Goals are how you want the world to be, and objectives describe what you will do to reach those goals.

Example

By September 2025, 300 future thinning and prescribed fire crew members from the Central Coast Region will be trained and red-carded.

Interim results state the expected changes in identifiable behaviors by participants or in identifiable approaches by interventions, systems, policies, or institutions as a result of what was gained (outputs) through project actions (activities). Progress at this level is a necessary precondition for achieving the objectives. Write intermediate results as complete sentences, as if already achieved. Put the targeted primary beneficiary group(s) whose behavior is expected to change as the sentence’s subject. Interim results may focus on demonstrable evidence of behavior change, such as adoption, uptake, or coverage.

Example

Training organizations will coordinate to identify 1,000 potential crew members from disadvantaged communities of the Central Coast to participate in comprehensive thinning and prescribed fire practical courses by 2023.

2.6. Next Steps#

Monitoring Plan. Once the situation assessment, theory of change, and programmatic goals/objectives are completed, it’s time to develop a monitoring plan. We will cover this in more depth in Chapter 3.

Project Plans. Project planning follows and can be driven and prioritized by your program strategy. See the project planning chapter for details.

Analysis and Learning. As your business or organization matures and your project experiences yield successes and data you track, it is time to analyze and learn from the results periodically. We’ll cover this in Chapter 3. However, reflective organizations/businesses learn the most from their experience, including mistakes, and use this learning to build a better organization. Don’t short-shrift this component! Set aside organizational time to complete it through regular analysis, learning, and writing workshops or strategic planning retreats.

2.7. Resources#

The Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation, developed by the Conservation Measures Partnership [CMP, 2020] is a definitive resource for program and project design.

ProPack I: Project Design Guidance for Project and Program Managers, developed by Catholic Relief Services [CRS, 2015] is a useful resource.

Business planning differs from organizational planning and typically focuses on developing a strategic business plan and pitch deck. See the Forest Business Alliance templates page for a business plan template.

Miradi is designed to help project proponents move through and plan the various stages of a program and projects and is widely adaptable.

ArcGIS StoryMaps are effective communication tools. FBA prepared a storymap about Spatial Business Planning as an example of how this powerful tool can be used with geospatial analyses for program or business planning efforts. However, it is not open source and can be difficult for some to access. For this reason, we have often switched to Jupyter Books for storymapping articles.

Geospatial analysis tools such as QGIS, Geemap, Leafmap, Google Earth Engine, R, and geospatial Python libraries are critical for planning forest conservation and businesses using spatial data and analysis. Looking for ways to integrate program design to guide geospatial analysis and the analysis to ratify or measure components created in the program design is a beneficial way to incorporate spatial data into planning.